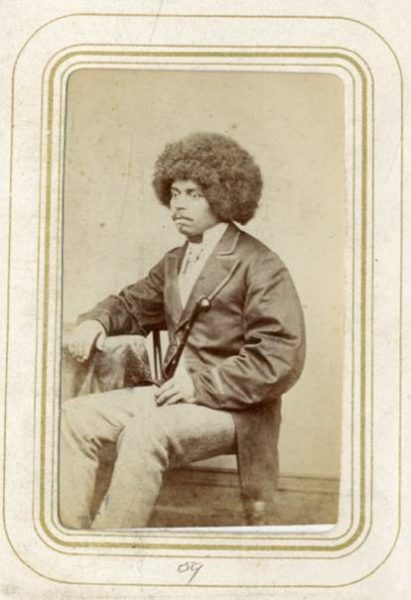

In our collections we hold the archives of the Oldham Photographic Society. The society is over 150 years old and still flourishing today. Amongst the many fascinating images captured by early members of the society one photograph stands out. It shows a young man of African descent. A young man who would have made quite a journey to walk the streets of Victorian Oldham.

The photograph was taken by William Thorpe and is in an album compiled by the Oldham Photographic Society in the late 1860s and early 1870s. It is a very remarkable photograph for its time and is the only example of Thorpe’s work in the album, so it appears that it is one of which he was proud. It doesn’t seem that William Thorpe was a professional photographer as his name is simply inked on the back of his pictures, probably with a simple rubber stamp. That much we do know. But who is the sitter for William Thorpe’s photograph?

The Life of James Johnson

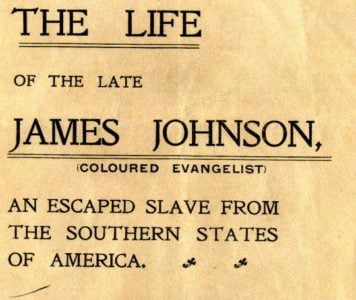

The most likely candidate is James Johnson. His remarkable story is recorded in an autobiography published after his death in 1914 by his daughter Alice. This small pamphlet of just 12 pages has a lengthy and descriptive title – ‘The Life of the Late James Johnson (Coloured Evangelist). An Escaped Slave from the Southern States of America. 40 Years resident in Oldham, England’. Only one copy of this publication survives and is held in the collections of Oldham Local Studies and Archives. It records the story of James Johnson’s early life in fascinating detail.

James was born into slavery in North Carolina in 1847. He records that “as to who my father and mother were I do not know; I have no recollection of them “. As a young boy he was the property of a boat builder and was later sold for $825 to a man named George Washington, under whom he worked on plantations and as a coachman.

Amidst the disturbance and confusion of the American Civil War James escaped and made his way to the coast. Somewhere near to Cape Fear he was able to board a warship named the Stars and Stripes which belonged to the Northern States. By this act of daring James Johnson became a free man. The naval ship eventually dropped him at New York and from there he made his way to England in December 1862. But his troubles were not yet over.

James Johnson comes to Oldham

In Liverpool the teenage James Johnson was soon robbed of what few possessions he had. He remembered his first months in England as “friendless and homeless” and he walked from town to town “where I took to singing, dancing and rattlebones, which…was easier than begging.” Later he joined a boxing troupe and performed at fairs around the country. In September 1866 James Johnson arrived in Oldham, possibly as part of the entertainment for Oldham Wakes. He decided to stay in the town and at first worked in the smithy at Messrs Dawson & Stanier’s Flat Top Foundry before later moving to the engineering firm of Platt Brothers & Co. Whilst at Platt’s he was introduced to the Sheffield Hallelujah Band and became a member of the Oldham Free Church.

James Johnson made a new life for himself in Oldham and is listed in the censuses as a blacksmith’s striker or iron striker. He also became known as an evangelist and preacher. In 1869 he married a local cotton worker, Sarah Preston “through whose instrumentality and patience I have acquired the blessed boons of being able to read and write”. After her death he married another local woman, Mary Ann Cook, with whom he had a daughter. James Johnson died aged 66 and is buried in Royton Cemetery in an unmarked grave. A more detailed account of James Johnson’s life has been published by American historian David Cecelski.

We cannot be sure that this photograph shows James Johnson. However the clues in the picture are promising. It shows a young man and at the time the album was compiled James would have been in his early 20s. The pose and clothing is typical of the late 1860s or early 1870s. And perhaps there is a further clue in the item he is holding? This large iron implement may be a slave collar. Although unlikely to be one from America it could have been made (by James himself?) in a local foundry as a prop to illustrate his story. We may never be certain but it is fascinating to speculate about the identity of the man in this remarkable photograph.