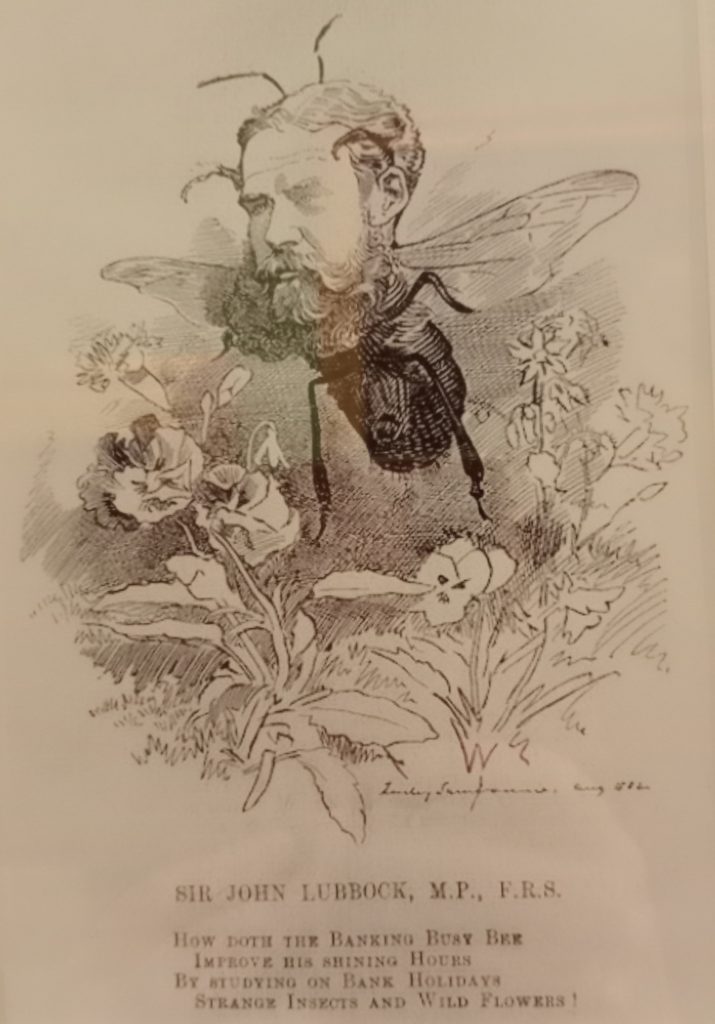

As part of our celebration of 175 years of the borough of Oldham we are sharing a series of guest blogs linked to items on display in our exhibition. These objects have been selected by staff, councillors, friends of Gallery Oldham and members of the public. This week Customer Experience Assistant, Jo Haigh, shares her discoveries about Sir John Lubbock and his pet wasp.

Sir John Lubbock, opened the old Library in 1883. Sir John Lubbock 1834 – 1913, was a scientist, biologist, author, writer, banker and Liberal Politician and it was him who introduced the Bank Holiday Act, Shop Hours Act, Open Spaces Act, Wild Birds Protection Act and Public Libraries Act to name just a few.

Sir John Lubbock became a very good young friend of Charles Darwin, he was only 8 years old when the Darwin’s became his neighbours at Down House in Kent, but John Lubbock soon became a significant part of Darwin’s life and work being a trusted friend and supporter.

He was also famous for training his pet dog to read, and for keeping a pet wasp until she died 10 months later. He donated her to The British Museum where she was prepared as a museum specimen and still remains as one of the highlights of their collection to this day.

Sir John Lubbock acquired the wasp in May 1872, he was visiting the Spanish Pyrenees when he found the female insect in a tiny nest with round 20 unhatched larvae. He brought her back to England with him on the train in a small bottle. Mournful of her state of being ‘alone in the world.’

In his 1884 book Ants, Bees and Wasps, Lubbock wrote:

‘I had no difficulty in inducing her to feed on my hand; but at first she was shy and nervous. She kept her sting in constant readiness; and once or twice in the train, when the railway officials came for tickets, and I was compelled to hurry her back into her bottle, she stung me slightly – I think, however, entirely from fright.’

‘Gradually she became quite used to me, and when I took her on my hand, apparently expected to be fed. She even allowed me to stroke her without any appearance of fear, and for some months I never saw her sting.’

Come the new year, Lubbock’s little lady, originally described as Polistes bimaculate but later revised to Polistes biglumis, took a turn for the worse. He wrote:

‘When the cold weather came on she fell into a drowsy state, and I began to hope she would hibernate and survive the winter. I kept he in a dark place, but watched her carefully, and fed her if ever she seemed at all restless.’

‘She came out occasionally, and seemed as well as usual till near the end of February, when one day I observed she had nearly lost the use of her antennae, though the rest of the body was as usual. She would take no food. (Two days later) she could but move her tail., a last token, as I could almost fancy, of gratitude and affection.’

She died in February 1873. Lubbock noted:

‘As far as I could judge, her death was quite painless.’

I love this story, a pet wasp of all things, and as fitting as she was as a pet for a man who wrote many books on hymenoptera including a bestseller, Ants, Bees and Wasps: a record of observations on the habits of the social hymenoptera. Such amazing important little insects.

Crazy and eccentric as it is!